Miranda Holmes-Cerfon

Department of mathematics

University of British Columbia

My work falls in three broad classes of mathematical approaches:

|

| © Slezak: Courtesy of NYU Photo Bureau |

- Physical and Biological modelling

- Computational Statistical Mechanics

- Computational Geometry and Rigidity Theory

Scientifically, much of my work is motivated by problems in materials science and soft-matter physics. These disciplines study how a great many small building blocks (like atoms, colloids, sand grains, blood cells, etc) come together to form something that we perceive on the macroscale as a continuous material. Understanding how the microscopic interactions between the building blocks give rise to the macroscopic properties of a material, or how a material evolves and responds to stress once formed, or how to design microscopic interactions to achieve a desired structure, are all areas where applied mathematics can play an important role. Mathematics can help to construct theories that simplify and make sense of patterns in complex systems, as well as to build computational tools to simulate systems more accurately or more efficiently.

One system of particular interest in my group are colloids. Colloids are particles with diameters of nano- to micro-metres that typically live in a solution, where they move around at random like a Brownian motion, and interact with each other in various ways. Colloids are studied experimentally for a lot of reasons, but one reason is their potential to form materials with novel properties, like new kinds of crystals, containers for drug delivery, nanoscale robots, materials that heal or replicate themselves, etc. Experimentalists have gained a wealth of control over features such as shape, size, charge, specificity, and valency of the particles, so an enormous variety of structures could potentially be assembled. My group develops theories and computational tools to solve the inverse design problem, which asks how to choose these parameters so a target structure forms efficiently.

Colloids share many features in common with some ingredients in living systems, such as proteins, viruses, and cells, a connection my group is beginning to explore.

This page is not an exhaustive description of my interests—if you have an interesting modeling roblem, please contact me about it!

Physical and Biological Modelling

|

| © Slezak: Courtesy of NYU Photo Bureau |

Many physical systems are incredibly complicated; if we wrote down equations describing all of the physics involved, we would never make sense of them, either computationally or analytically. Physical modeling involves figuring out what is the best set of equations that simply but accurately describes a particular system, and then, making predictions about physical phenomena from these equations. Often this involves writing down complicated equations, and then identifying small or large parameters so the equations can be simplified, for example using perturbation theory or homogenization techniques. Some questions that my group is interested in include:

- How do oysters filter water, and where in a body of water should oysters be placed in order to maximize the overal filtration rate? We hope to make models and predictions for the New York City Harbour, in collaboration with the Billion Oyster Project.

- How can we describe the dynamics of colloids coated with sticky DNA strands

(a common technique to design interactions between colloids), without tracking the dynamics

of each individual DNA strand? Do DNA-coated colloids actually "roll", or can they slide?

This problem is similar to problems in biology, such as in understanding how an influenza virus enters a cell, or how a white blood cell exits a blood vessel. - How does hydrodynamics (interactions between colloids caused by the ambient fluid) affect the dynamics of colloids? And, how can we incorporate friction between the surfaces of colloids, into a description of their stochastic dynamics?

- How can we model the free energy landscape and dynamics of particles with very short-ranged attractive interactions? Such is the case for colloids, and traditional theories to address such questions don't work as effectively for such interactions; furthermore numerical methods are slow since the interactions are so stiff.

- Why does a small number of marbles swirled in a teacup, rotate in the same direction as the swirling, but a large number of marbles rotates in the opposite direction? Amazingly, this question also has something to do with why and how a hoola-hoop levitates.

Computational Statistical Mechanics

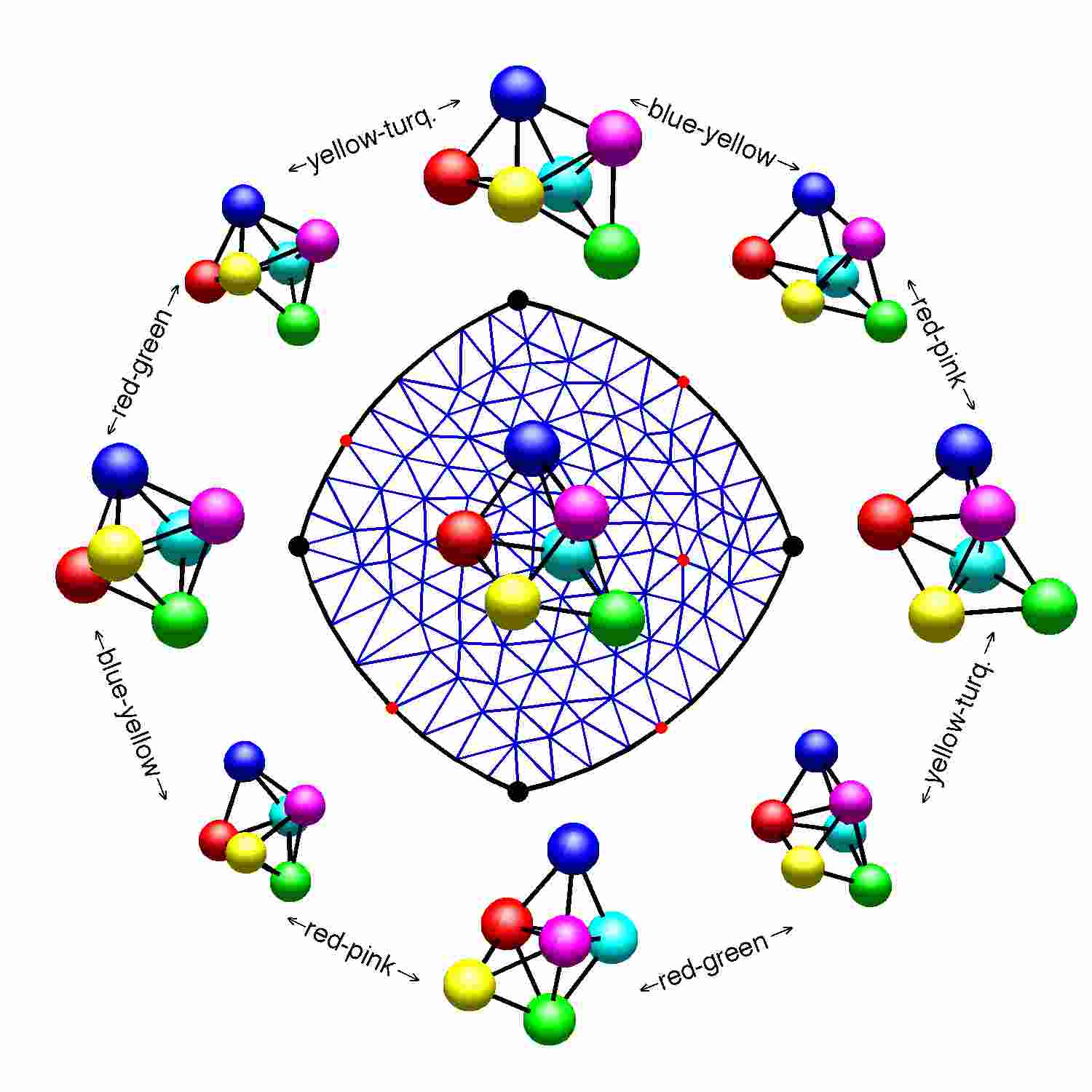

My group builds algorithms to compute the statistical mechanical properties of physical systems subject to constraints. One common example of a constraint is a distance constraint between particles. Mathematically, this means we build algorithms to perform calculations on manifolds, or their generalization, stratifications, which are collections of manifolds of different dimensions that are glued together at their boundaries. We develop algorithms to sample a probability distribution on a manifold or a stratification, and to simulate a stochastic differential equation on a manifold or a stratitication. We are also interested in solving inverse problems in statistical mechanics, for example to ask how can one design particles so a particular target state is low free energy, kinetically accessible, or both?

Computational Geometry and Rigidity Theory

Much of my group's work is informed by geometry, and particularly rigidity theory. We study the configuration spaces of frameworks, graphs embedded in a particular space with distance constraints on the edges, and their generalization tensegrities, frameworks where some edges can stretch and some can compress. We study how ideas developed to understand frameworks and tensegrities can bring new insight into the statistical mechanics of materials (like colloids), how they can lead to better simulation strategies for systems with constraints, and, we are interested in designing frameworks and tensegrities to perform various functions, or that can assemble themselves. A recent interest is in applying these ideas to study the statistical mechanics of nanoscale origami, which is not only a beautiful art form made miniature, but is also a promising technique for engineering nanoscale structures.

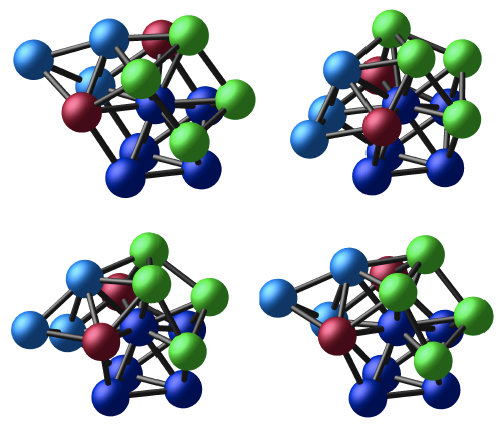

One simple question where geometry gives insight into materials is: How many ways are there to arrange N hard spheres in space, so they form a rigid cluster? This is a mathematical question, but the solution could bring insight to a range of problems, including what structures colloids can assemble into and how they might do it. It is also a challenging computational problem that brings up interesting issues in rigidity theory and numerical algebraic geometry. The data generated by my algorithm to attack this problem is on the sphere packing data page.